The story of the first Dutch red cycling path

Last december Vienna’s very first red cycling street was opened. With the help of a Dutch cycling consultant (yes we have those). An article about the Vienna cycling street showed me that the energy transition leads to renewed interest in our cycling culture and our cycling paths and streets. One of the most asked questions the Dutch Cycling Embassy gets is why they are red.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the start of plans in a city named Tilburg for the construction of the very first red cycling route in the Netherlands. The man who ‘arranged’ those first 10 kilometers became red is someone I know very well and he now is 92. So I decided to finally spend some time on connecting our memories with information from the city archives to share how that happened in a period that shows remarkable parallels with our current time. And to also tell you how the Netherlands turned into a cycling country in the eighties.

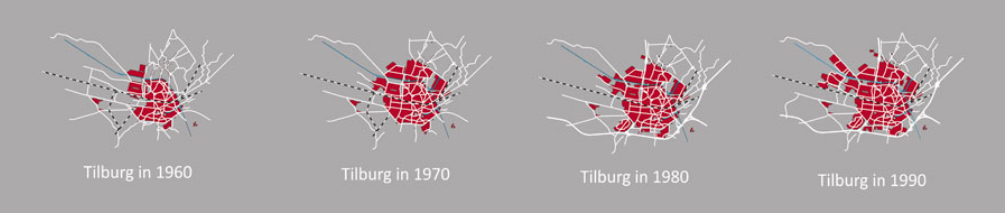

Tilburg is the seventh city of the Netherlands. After the Second World War it was one of the Dutch Cities that wasn’t able to build enough houses for the growing population for years. As a ’textile city’ Tilburg also had to undergo a transition. There were no industrial areas outside cities yet and the city within its ring roads consisted of seven townships that had grown together. With many textile factories in between them. Because an increasing part of the textile industry was moving to countries with lower wages, many local manufacturers closed down their business.

A mayor who saw that the city had to change

Tilburg had a mayor called Cees Becht who had good advisors and saw that the city needed to change drastically to build enough housing for the growing and changing population. He managed to convince the city council to reorganize the local Public Works Department and to expand it with a new ‘Main Department of Spatial Planning’ containing the departments of Urban Development, Public Housing, Land Affairs and Traffic.

Three young urban planners and one young traffic engineer named Rob Sangen were hired. Together they got the task to make a (structural) plan for the old city to build approximately 10,000 homes on the vacant and soon to be vacant factory sites inside the ‘ring roads’. Mainly small housing units for young people and senior citizens.

To lead the new department, the mayor wanted a director who had a lot of experience with the realization of large projects, among other things. So that the 10,000 homes inside the ring roads as well as 20,000 new homes outside the ring roads would be built as quickly as possible.

After studying Road and Hydraulic Engineering at the Technical University in Delft, my father worked for several contractors and for Rijkswaterstaat for a number of years on large projects (roads with tunnels, viaducts and bridges) throughout the country. Early 1973, my mother wanted to return to the province of Brabant to live closer to her family. When my father showed her the vacancy in Tilburg, she encouraged him to apply and he got the job.

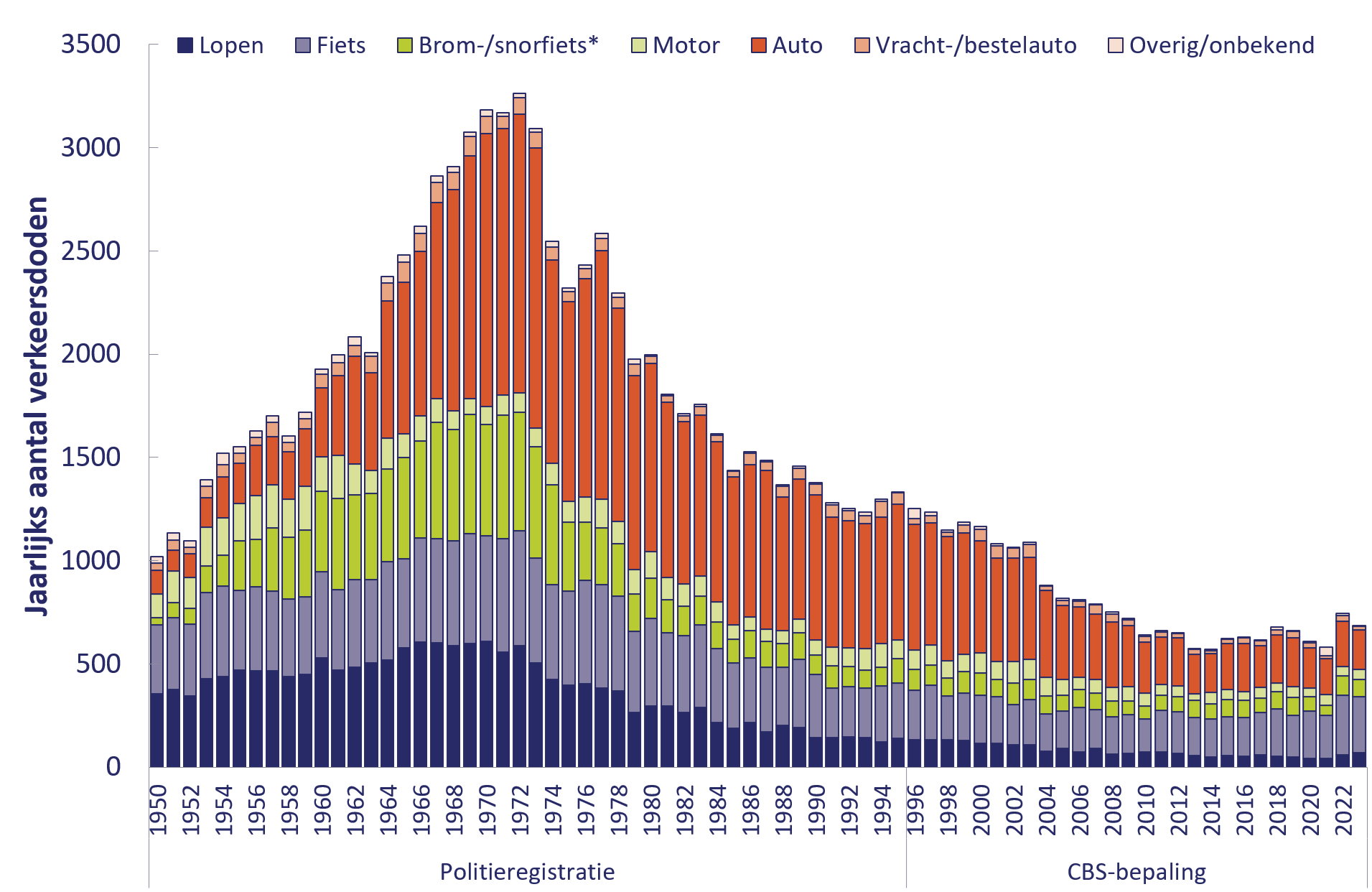

A bizarre number of more than 3000 traffic deaths a year

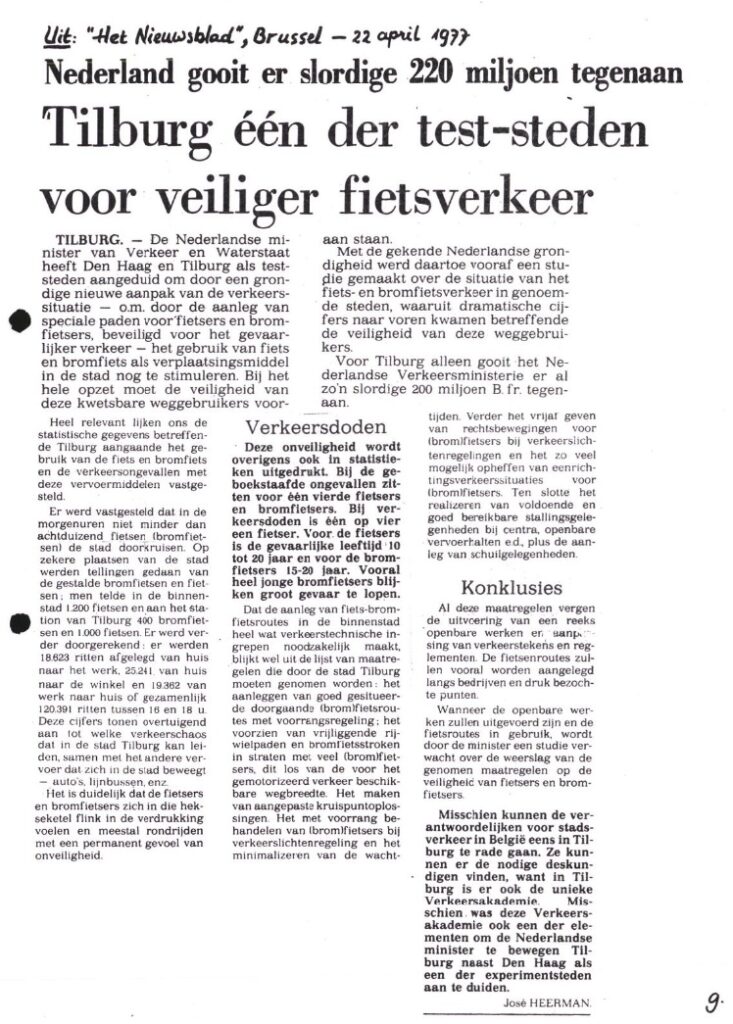

The enormous growth in the number of cars in the 60s and 70s resulted in more and more traffic accidents. Thousands of people died each year, including hundreds of children. Among them was the 7-year-old son of politician Tjerk Westerterp. When he became Minister of Transport and Water Management in 1973, an action group had been set up by another father whose child had died in an accident, called ‘Stop the child murder’.

Minister Westerterp wanted to spare other parents his grief and supported many initiatives to increase safety in traffic for all types of users. He also had an extensive ‘Multi-year Plan for Passenger Transport’ written, which he would present on Budget Day 1975.

Tilburg heard that 25 million guilders (11,3 million euros) had been reserved for 1976 for a ‘demonstration project for cycling paths’ in two cities. Rob Sangen had already almost completed his future plans for cycling in the city and informed about the conditions for the cycling path.

It had to be: a cycle path right through a medium-sized or large city (1), it had to include elements such as bridges, viaducts, priority intersections and car-free streets (2), they required research into the effects of the new cycling path (3), only extern costs were financed, the city had to pay the hours of civil servants involved (4) and it had to be finished before the deadline of the Department of Transport and Water Management (5). Registration had to be done with two former colleagues of my dad at Rijkswaterstaat (the department that builds all national roads, bridges, viaducts etc).

A safe cycling path through the centre of Tilburg

Based on his plans for special cycling paths in Tilburg Rob Sangen with the help of Peter van Gurp, director of the recently founded National Traffic Academy, could quickly make a rough sketch of a cycling route for the demonstration project. It ran from east to west and through the heart of the city. [For those familiar with Tilburg: from just past the Ringbaan Oost, via the Tivolistraat, Heuvel, Pieter Vreedeplein, Tuinstraat, Lange Schijfstraat and Boomstraat under the Ringbaan West to Tilburg University.]

With the approval of the city council, my father shared the sketch with his former colleagues at Rijkswaterstaat. They were interested but needed a more specified design and a solid implementation plan.

Rob Sangen and Peter van Gurp worked very fast and Peter came up with the idea of extending the cycling path with a cycling bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal and all the way to two villages (Berkel-Enschot and Oisterwijk). This would also allow a study on the influence of good cycling paths between commuter villages and city centers. According to him, this would complete the study.

The strict deadline of the Minister

In order to meet Minister Westerterp’s deadline and to get the project through the municipal council, Tilburg split the plan into three separate projects. They suggested three different design agencies and three different contractors. This way, the city’s employees would not get any extra work. The agencies and contractors would have to sign a contract with very strict deadlines.

The approach with hiring six companies to do the work gave Rijkswaterstaat the most confidence in Tilburg to complete the project on time. So in addition to the obvious first city The Hague (the residency of the Dutch government) Tilburg became the other city that received millions.

The Aesthetics Committee recommended yellow

For the sake of clarity Rob Sangen and my father wanted to give the cycling path a different colour than the grey pavements and roads. In the obligatory consultation the city’s Aesthetics Committee chose yellow. Because of the diversity of the houses and facades in the narrowest of three soon to be ‘car-free streets’. They didn’t discuss if another colour might be safer or cheaper.

My dad knew that grey concrete tiles cost about ƒ4.50 per m2. He asked one of his buyers to inquire about the available colours of concrete tiles and their prices at the company Struyk Beton in nearby Oosterhout who was the tile supplier of the city. He learned that yellow concrete tiles had the highest price at ƒ14 per m2. Red was the cheapest colour at ƒ9.00 per m2.

My dad liked red tiles just as much as yellow ones because the other streets where the cycling path would come were full of red brick facades. He contacted Tim Stoop, the sales manager of Struyk Beton whom he gotten to know during his college internship. He negotiated the price for red tiles for the demonstration project down to ƒ6.50 per m2. With a price less than halve of the one for yellow tiles the aesthetic committee agreed to the colour red.

On April 21, 1977 a proud Minister opened ‘The Red Cycling Path’

The city received an additional 3 million on top of the 12 million already promised to also build the cycling bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal and the commuter cycling path. This allowed for the construction of more than 10 kilometres (6 miles) of cycling path.

The Hague worked much slower than Tilburg. Together with the projectleader from Rijkswaterstaat they also chose red following Tilburg. The Hague did not meet the Minister’s deadline at all and the last part of the Tilburg cycling path to Oisterwijk also wasn’t finished on time.

But less than 24 months after the first contact between the department and Tilburg, a proud Minister Westerterp cycled from west to east through Tilburg. With the members of a local cycling club in front of him and together with local bigwigs and the people who had been involved in the realization of the project. Just a month before the next general elections on May 25, 1977.

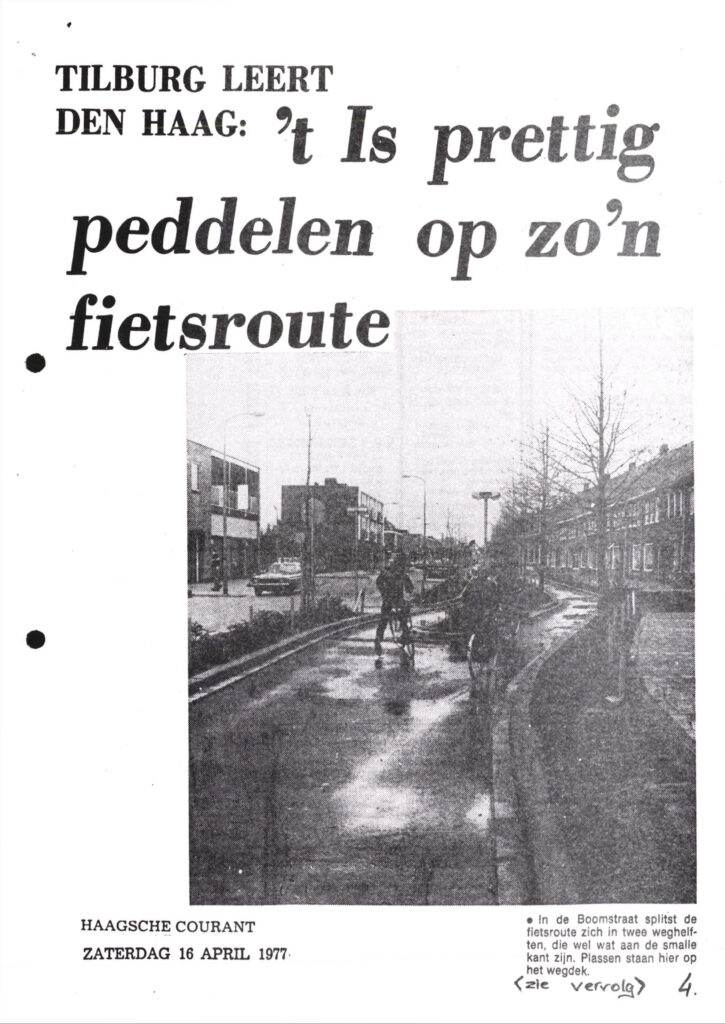

The cycling path in Tilburg got a lot of free publicity

In three streets the red carpet was laid out for cyclists and from that moment on there was much less space for cars. Because what became known as ‘The Red Cycling Path’ was finished just in time and was opened by a well known politician, it received a lot of national and international publicity.

According to a national newspaper the Minister’s multi-year plan not only reserved 25 million for 1976 for safe cycling paths. He also reserved 35 million for 1977 and for the years after that, an amount that increased to 51 million in 1980. The total budget was around 220 million. The Department had taken those millions from the National Road Fund and were actually intended for the construction and maintenance of motorways.

Tilburg became the example for other Dutch cities

During the construction of the cycling path in Tilburg representatives from multiple cities and towns came to see the demonstration project. At the opening it was already known that with the 35 million available for 1977, at least eighteen cities would also build safe red cycling paths and streets from the suburbs to the centre. Followed by more Dutch cities in 1978, 1979 and 1980. All with a subsidy of 80% of the costs by the national government.

In December 1977 Tilburg and the Traffic Academy organized a convention on ‘the (moped) cyclist and his facilities.’ That day 20 experts and people who were involved in the demonstration projects shared their vision on how to deal with cyclists and moped riders in cities and villages in the future. Tilburg became the Cycling City of the Netherlands and stayed that for years. And because of all the millions spent on safe cycling paths and streets between 1976 and 1981 we became a cycling country long before other countries.

And the men responsible for the first red cycling path?

In the years that followed, Rob Sangen talked to dozens of delegations from other cities (as far away as Tokyo) about the experiences with that first safe cycling route. And about the ‘star network’ with red cycling paths and streets to all outskirts of Tilburg built under his leadership. To then go on to lead the Traffic and Transport department in that other city, The Hague.

Peter van Gurp remained director of the Traffic Academy until it moved to another city years later. He and his students helped with the research into the effects of safe cycling paths.

A few years later, Tim Stoop became commercial director at Struyk Beton and sold a enormous amount of red concrete tiles.

A friendly lady from Struyk Verwo Infra (the successor to Struyk Beton and almost 50 years later supplier of eco-friendly paving materials for Tilburg), told me on the phone that red concrete tiles are still much cheaper than yellow ones due to the price of the dye. An equally friendly lady from Ventraco, supplier of sustainable dyes for asphalt (which most cycling paths are made of nowadays), told me that red is also the cheapest colour for asphalt – after grey and black.

And my dad? He continued to work on the future of Tilburg outside the spotlight for another 15 years. After he retired in 1992, he moved to the town Tim Stoop lived in. Through a mutual acquaintance, Tim joined a club that my father had co-founded. The 92- and 93-year-olds last talked to each other yesterday. I don’t think they have any idea how many kilometers of red cycling path has been constructed after those first 10 kilometers.

What happened to the ‘The Red Cycling Path’

Ironically nowadays the narrow street in Tilburg that was the reason for the original choice of the color yellow, is the only remaining red cycling street of the first three streets. The city government hasn’t realized how much the rest of the world is interested in the Dutch red cycling paths and has not made it a tourist attraction yet. It is the ‘Boomstraat’ between the ‘Noordhoekring’ and the ‘Populierstraat’ in case you happen to be in the neighborhood and want to cycle there. ;o)

In 1978 the Danish filmmaker Leif Larsen filmed in Tilburg and in 2018 Bicycle Dutch made this new video on whats left of the first Red Cycling Path.

Apart from a few streets and squares in the city centre, Tilburg still has a large network of safe red cycling paths to all corners. There are also so-called ‘fast cycling paths’ to the surrounding villages.

Fortunately, not all textile factories were demolished or converted into homes. Two of the most beautiful buildings became museums. In the municipal Textielmuseum you can experience the history of a textile city and the private and internationally renowned Museum De Pont offers exhibitions of contemporary art.

History repeats itself. In the Netherlands we are once again facing a housing shortage, which makes it difficult for young people in particular to get their own home. And we are once again in the middle of a transition. The energy transition means that we have to change our cities, rural areas and lives, and that there is interest from all over the world for the energy-efficient Dutch cycling culture and the infrastructure with red cycling paths and cycling streets.

Unfortunately we also have more and more traffic accidents with young victims on bicycles. Let’s hope ‘we’ can solve these and other problems again.